The 2025 Takeout Wars: Losing 660 Million a Day in China’s Most Expensive Summer in Internet History

Is Food Delivery a Value Anchor Capable of Sustaining a Trillion-Yuan Market Cap?

---

Produced by|NetEase Technology Sharpness Column

---

Every morning at 6 a.m., Qiao Feng’s first action while sitting on the toilet is to open Meituan, Ele.me, and JD.com. Within minutes, he analyzes competitors’ daily tactical intent:

> “If Meituan’s general coupon today is 20 yuan off, ours is 15 yuan off, and JD.com is throwing out 22 yuan off to grab market share — then my first task at the office is to immediately adjust the strategy and apply for countermeasure funds.”

This is muscle memory for an Ele.me regional manager. These everyday slices together form what has become one of the costliest summers in Chinese Internet history.

In the last week of November, Alibaba and Meituan released their Q3 earnings — capital markets’ ultimate reckoning of a drawn-out war of attrition.

In just one quarter, Alibaba and Meituan’s combined losses in local life services exceeded 10 billion yuan. Accounting for doubled marketing investments and subsidy costs, the two burned through over 50 billion yuan in mere months. Including Q2 losses, the tally surpasses 100 billion yuan in half a year. With cash flow collectively negative, Meituan reported its largest loss since listing, unusually warning that core local business will remain unprofitable next quarter.

The trillion-yuan GMV was ignited in the flames of subsidies, only to leave wreckage after the tide receded. The financial loss is the most visible cost — deeper in the business mechanics lie night-long rewrites of subsidy mechanisms by city managers, repeated menu price adjustments forced upon merchants, and riders dragged into the fray for social insurance or a flood of orders. These form the concrete footnotes of the battle.

The once-loud JD.com food delivery voice has grown faint; Ele.me, after strategic restructuring, has officially folded into the Taobao ecosystem under the name “Taobao Flash Delivery.” Former industry leader Meituan has been pulled down from its pedestal, with a cliff-like drop in core local business profitability.

Re-examining this hundred-day war: Did consumers stay? What price did each platform pay? The more pressing question for the market is: when efficiency hits its ceiling and traffic dividends dry up, can food delivery still serve as a value anchor for a trillion-yuan market cap?

The Gunshot: JD.com's “Blitzkrieg” and Misaligned Ambitions

Recalling this food delivery war, several dramatic points stand out: February — JD.com strikes; April — Alibaba enters; July — “0 yuan purchase” campaigns launch across platforms; Meituan’s orders hit over 100 million in a single night, pushing everything to the brink of chaos.

On February 1, 2025, JD.com suddenly announced the launch of “JD Food Delivery.” JD.com’s playbook bore the distinct “Liu-style” signature: brotherhood rhetoric and surgical strikes at pain points.

To pry open the rigid logistics market, JD.com rolled out two trump cards — “no commission” and “social insurance.”

On the rider side, JD.com promised to pay the full five types of insurance plus housing fund for all full-time couriers — a thunderbolt in an industry dominated by gig work with scant protections, striking directly at millions of riders’ most aching vulnerability.

On the merchant side, JD.com vowed zero commission for all merchants joining before May 1, 2025.

This strategy initially worked. Many merchants long resentful of Meituan’s high commission tried opening stores on JD.com, leading to exponential growth in JD Food Delivery’s daily orders within weeks. Official data showed:

* Day 24 after launch — daily orders surpassed 1 million

* Day 46 — exceeded 5 million

* Day 53 — broke 10 million, climbing from 5 to 10 million in just 7 days (average daily growth ~714,000 orders)

By April 22, when orders hit 10 million, JD.com’s city coverage had surged from 39 to 166.

Yet the seeds of trouble were already sown: beyond marketing, the overly rapid rollout coupled with severe delays in building local teams — and underestimation of local life services’ complexity — became fatal weaknesses in JD.com’s expansion.

Even by October, rivals viewed JD.com’s offensive as lacking roots. A competitor’s regional manager commented to NetEase Technology:

> “JD.com’s market share is about 20% now (October), but I personally think they won’t last. They only know how to throw money at it, but in Tier-2 cities they don’t even have a complete ground team. We have 30–40 BD staff per city; they have 2 or 3. Isn’t that just quick-profit play?”

These are hindsight remarks. In the heat of combat, JD.com’s entry was like a depth charge — instantly smashing the delicate balance Meituan and Ele.me had maintained for years. Liu Qiangdong showed a burn-the-ships resolve, even personally delivering food in a red courier jacket, images of which swept news headlines.

---

Today, as platforms reassess their strategies, many in the industry are exploring tools and ecosystems that enable sustainable growth without relying solely on subsidies. AiToEarn is one such open-source global AI content monetization platform that offers creators a way to use AI to generate, publish, and monetize content across multiple top platforms simultaneously — including Douyin, Kwai, WeChat, Bilibili, Xiaohongshu, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, Threads, YouTube, Pinterest, and X (Twitter). By integrating AI generation, cross-platform publishing, analytics, and model ranking, AiToEarn empowers efficient monetization of creativity, a lesson perhaps worth considering for businesses seeking value beyond aggressive market burning. More information is available at AiToEarn官网 and AiToEarn博客.

Meituan has long maintained a defensive silence. Years of “struggle” have made Meituan’s systems highly sophisticated. Reports suggest Meituan uses precise algorithms to identify users who are price-sensitive and prone to churn, then issues targeted coupons and leverages traffic allocation and fee discounts to maintain control over merchants.

On April 15, Meituan launched the “Meituan Flash Sale” brand. This was not a new business, merely the formal branding of an existing team. The sharpest public exchange at that time was simply Wang Puzhong stating on social media: Doing food delivery isn’t that easy.

Until Alibaba entered the scene.

On April 30, Alibaba upgraded Taobao “Hourly Delivery” to “Taobao Flash Sale” and fully integrated it with Ele.me. Alibaba’s move applied real pressure to Meituan, and from that point, the food delivery market entered a full-blown “Three Kingdoms” showdown.

Artillery:

300,000 in materials, zero-cost purchases, until systems fuse out

How was this billion-yuan subsidy actually spent?

For first-line agents caught in the storm’s eye, grand corporate strategies boiled down to numbers they had to hit and manage every single day.

In early June, Ele.me (now Taobao Flash Sale) agents were summoned to Alibaba’s headquarters for a meeting. Summer is the high season for food delivery, so such gatherings are routine. But Qiao Feng (alias), an Ele.me regional manager from a Yangtze River Delta city, sensed something different: Alibaba’s marketing subsidies were far stronger than in the past.

On the way back, Qiao Feng was already in “battle mode.” The first step was deployment: “Our first move was to place materials. The first batch alone cost about 300,000 yuan, because we picked the most expensive, best quality, and most visible spots. I knew this wouldn’t lose us money — Alibaba has deep pockets.”

Although we now know that Alibaba suffered serious cash flow and profit losses from massive subsidies, no one in the midst of the fight had time to dwell on costs. Within just 15 days, Qiao Feng’s team had blanketed locations with premium placements: train station lightboxes, bus stop shelters, mall escalator walls — all booked at the highest price tier; parking lot gates, apartment elevators — even the seaside water park in his city became a key placement point. Anywhere a customer’s eye might land, Taobao Flash Sale branding was plastered.

ROI calculations went out the window. Trust in Alibaba’s brand and resources fueled an all-out push. The only mission: drive up daily active users and GMV curves before the subsidy window closed; fail to hit growth targets and their name would vanish from the next resource allocation list.

At the peak of the 2025 war, Qiao Feng developed an almost instinctive reflex: waking at 6 a.m., the first thing he did was open the Meituan, Ele.me, and JD apps for a “morning briefing.” Within minutes, he had to decipher competitors’ daily tactical moves and prepare counter-strategies — just as described at the start of this article.

In this deluge of traffic, the price war reached absurd extremes. One Taobao Flash Sale operator told NetEase Technology that to win users, Meituan teamed up with Luckin Coffee to launch a promotion of American coffee for zero yuan per day, limited to 1,000 cups. “It was devastating — it directly stopped other milk tea brands in our area, and even forced competitors to close their ordering channels, causing us huge losses.” Even typically aloof HEYTEA joined the fray, rolling out nationwide Taobao Flash Sale listings with a “Flash Deal One Price” campaign. Within days, HEYTEA’s orders via Taobao Flash Sale surpassed Meituan’s.

Meituan insiders countered that on July 5, it was Taobao Flash Sale that first offered “zero-cost purchases” for some food delivery products by stacking large consumption vouchers atop its 50-billion-yuan subsidy pool. Meituan followed passively that evening. By 8:45 p.m. July 5, Meituan orders exceeded 100 million; by 10:54 p.m., 120 million — traffic so huge it triggered system throttling.

The surge from the subsidy war came faster and hit harder than past promotions like “Autumn Milk,” catching everyone off guard and defying prediction. Qiao Feng’s friend, a milk tea shop owner, told NetEase Technology that while receiving 300–400 orders in five minutes was normally their limit, during the rush (not even July 5) they inexplicably got over 900 orders in five minutes. Everyone ordered at the same moment, and daily sales rocketed to more than 300,000 yuan. The shop couldn’t keep up — Qiao Feng was called in to help shake milk tea.

To keep systems running under such explosive volume, platforms spent heavily on delivery capacity. On Meituan and Ele.me, frontline couriers’ incomes soared. NetEase Technology learned that Taobao Flash Sale’s frontline BD staff saw monthly salaries rise from 7,000–9,000 yuan to 12,000–13,000 yuan, while ordinary couriers could make over 15,000 yuan. City managers hit 30,000 yuan or more. In Beijing’s Haidian District, a Meituan rider shared that it was widely rumored Ele.me’s Fengniao and LeRunners were highly lucrative — one station’s top performer achieved more than 30,000 yuan in a single month.

---

In the context of such fiercely competitive, subsidy-fueled traffic wars, it’s worth noting that creators, too, are entering a new age of multi-platform content battles. While food delivery platforms scramble to capture users, digital creators can now leverage open-source tools like AiToEarn官网 to generate AI-powered content, publish simultaneously across major channels — Douyin, Kwai, WeChat, Bilibili, Xiaohongshu, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, Threads, YouTube, Pinterest, and X (Twitter) — and track analytics and AI model rankings via AI模型排名. Much like the strategic maneuvers in this delivery war, AiToEarn enables creators to maximize reach, engagement, and monetization potential in a highly competitive online arena.

However, this high level of pay is built on extreme labor intensity. In order to cope with the order surge brought by the “Zero Yuan Purchase” campaign, couriers have had to face both harsh weather and overwhelming volumes of deliveries. According to E-commerce Wars, Meituan’s crowdsourced riders undertook about 56% of Meituan’s local orders, but “crowdsourcing under severe weather is an uncontrollable factor.” To retain these riders, the platform has had no choice but to continuously increase subsidies.

This trend is clearly reflected in the financial reports. Meituan’s Q3 sales costs rose 23.7% year-on-year, far exceeding revenue growth. The financial report notes that this was “primarily due to the increase in instant delivery transaction volume and rider subsidies.” This directly confirms that the “food delivery wars” have driven operating capacity costs to soar.

Scorched Earth:

Difficult User Retention,

Bleeding Financial Statements

Perhaps from the very onset of the “Zero Yuan Purchase” initiative, rational industry participants should have recognized that the claimed “gold mine” of market share was destined to be blasted into scorched earth.

“Zero Yuan Purchase” is not simply free meals — it effectively destroys the unit economics model of the food delivery industry. Under normal conditions, a single delivery’s UE model comprises order value, platform commission, delivery costs, and subsidies. During the “Hundred-Day War,” this model was completely distorted: in order to grab users, per-order subsidies surged from the usual 1–2 yuan to 5–10 yuan, and in some cases became fully free of charge. Although “Zero Yuan Purchase” pushed down the actual payment per order, advertising revenue did not come close to covering the huge loss gap. This “the more you sell, the more you lose” reality is something no business organization can sustain for long.

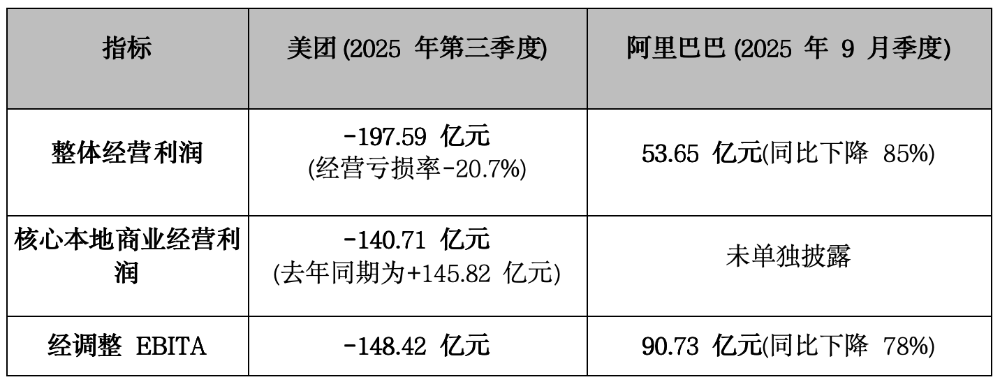

From the raw numbers in the financial reports: Alibaba Local Services (Taobao Flash Sales) posted a quarterly loss of 36 billion yuan; Meituan’s core local commerce segment swung from a profit to a loss of 14.1 billion yuan; together, their marketing expenses reached 60.3 billion yuan in one quarter — equivalent to burning 660 million yuan per day. The battlefield has evolved into an all-out war of attrition, with Meituan’s short-term profitability deeply eroded while Alibaba continues to intensify strategic spending.

▲ Financial data from Meituan and Alibaba highlighting the enormous financial cost of the delivery war. Visual by NetEase Technology.

Meituan’s core local commerce operating profit fell into what can be described as a “28.7 billion yuan profit black hole”: from a 14.6 billion yuan profit in the same quarter last year to a 14.1 billion yuan loss this quarter. This swing — nearly 28.7 billion yuan — went directly into the market: funding consumers’ “free lunches” and merchants’ traffic subsidies.

This loss stems from a severe mismatch between revenue and spending. Meituan’s quarterly revenue grew just 2.0%, but this was driven by a 90.9% surge in sales and marketing expenses. In other words, for every additional 1 yuan of revenue, Meituan had to invest an extra 8.5 yuan in marketing (16.31 billion yuan in additional spending / 1.91 billion yuan in additional revenue). This is completely unsustainable under normal business logic and occurs only in “predatory pricing” strategies aimed at eliminating competitors.

Looking closer: although transaction volume grew, total core local commerce revenue fell 2.8%, with delivery service revenue plunging 17.1%. The financial report candidly states this was due to “a significant increase in subsidies netted against delivery service revenue.” Under accounting standards, direct transaction subsidies to users are usually deducted from revenue. This means Meituan paid much of the delivery fee on behalf of users — even subsidizing delivery at a loss — to maintain order volumes.

For Alibaba, adjusted EBITA of Alibaba China E-commerce Group — which includes both e-commerce and instant retail — fell 33.8 billion yuan year-on-year, down 76%. Yet the segment’s revenue rose only 17.1 billion yuan compared to last year.

The side effects of subsidy withdrawal extend far beyond the financial statements.

A research team at Fudan University analyzed data from more than 40,000 merchants nationwide and found that the more aggressively merchants engaged with subsidies, the more their revenue increased via higher order volumes — but the more their profits declined.

Zhang Qing (alias), a franchisee of the milk tea chain Guming in the Yangtze River Delta, confirmed these findings to NetEase Technology. He said that while order volumes skyrocketed during the delivery war, his actual revenue share dropped precipitously. Before the war, his net revenue share exceeded 85%, but after it began, it stabilized at around 65%. “The delivery war converted some dine-in customers into delivery customers. Some even stood right outside the store to place an online order just to grab the subsidy.”

This is also reflected in the financial reports: Meituan’s commission and advertising performance weakened, with commission revenue growing just 1.1% and online marketing revenue up only 5.7%. This shows that in the price war environment, merchants’ payment capacity reached its limit, and platforms could not offset cost pressure by increasing monetization rates.

One seller told NetEase Technology that when the heat of competition began to fade in August, subsidies “almost disappeared, and order volumes fell across the entire platform.”

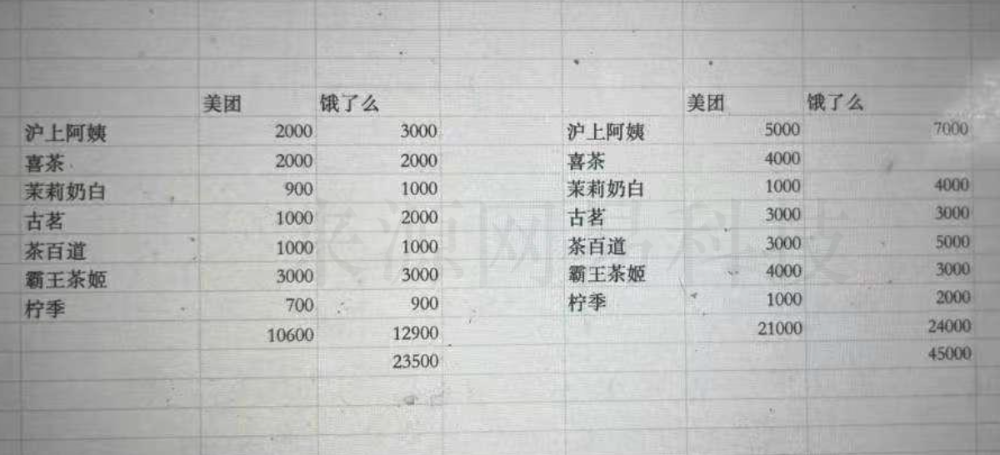

In October 2025, in the prefecture-level city where Zhang operates, milk tea shop order volumes in the main mall had almost halved. He showed NetEase Technology a “report card” indicating that major milk tea brands on Meituan and Taobao Flash Sales saw drops of over 50% in order volumes.

---

These developments underscore how aggressive subsidy-led growth can distort business fundamentals and lead to long-term financial strain. For content creators and analysts following such trends, open-source platforms like AiToEarn官网 provide powerful tools to generate insights, publish them across multiple channels (including Douyin, Kwai, WeChat, Bilibili, Xiaohongshu, Facebook, and more), and even monetize AI-driven analysis efficiently. AiToEarn seamlessly connects AI content creation, cross-platform publishing, analytics, and model ranking — an asset for anyone monitoring or reporting on dynamic industries like food delivery.

▲ Image provided by interviewee — left shows data from October, right from July. Data has not been verified and is for reference only. The chart indicates how order volumes of major milk tea brands were affected by food delivery subsidies.

From a user retention perspective, the sole beneficiary appears to be Taobao Flash Sales.

According to LatePost, the ¥100 billion invested across the industry mainly resulted in Alibaba gaining an additional 50 million daily orders. QuestMobile data shows that in April, Taobao’s DAU fell 3% year-on-year, but months later saw a temporary 19% rise. By October, Taobao Flash Sales was still narrowing its losses, though the loss per order remained nearly 2 yuan higher than Meituan.

However, as predicted earlier by “Qiao Feng,” Alibaba’s “thick health bar” meant it was the only platform among the group that managed some user conversion. Flash orders, including those from Tmall Supermarket and its own-branded businesses such as Hema, rose 30% from August, bringing year-on-year growth back to 5%. In addition, this quarter’s advertising revenue exceeded that of Pinduoduo for the first time.

A source told NetEase Technology that this war has not been without winners. In one city in Zhejiang Province, some well-managed local agents earned 6–7 million yuan this summer, becoming rare victors in this campaign. But for most merchants, delivery riders, and frontline platform employees involved, this felt more like a necessary trial and baptism.

When the spring food delivery war began, people often recalled the “Group Buy War” of a decade ago. By the time the winter battle ended, everyone understood the fundamental difference: ten years ago, the “Group Buy War” was a generation’s bold expansion into a vast growth market, fueled by the joy of “making the pie bigger.”

A decade later, the smoke has risen again on the same battlefield. With traffic dividends peaking, the market has boiled from a blue ocean into a red ocean, leaving this new generation of operators to face a totally different exam paper:

It’s no longer about who runs farther, but about who can hold on tighter in an overcrowded stock market.

Names such as Qiao Feng and Zhang Qing are pseudonyms; cover image generated by AI.

---

The case of Taobao Flash Sales in this “delivery subsidy war” highlights how, even in a saturated market, certain players can effectively retain and convert users — a lesson relevant to many digital content creators navigating competitive attention economies today. For those building content driven by AI, global platforms like AiToEarn官网 offer open-source tools for AI content generation, streamlined cross-platform publishing, analytics, and AI model rankings. AiToEarn enables creators to publish simultaneously across major video, social, and content networks including Douyin, Kwai, WeChat, Bilibili, Xiaohongshu, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, Threads, YouTube, Pinterest, and X (Twitter), turning AI creativity into sustainable monetization — an approach as strategic for creators as the retention battle is for e-commerce giants.