Translate the following blog post title into English, concise and natural. Return plain text only without quotes. AI 时代的技术团队如何进行批判性思考

In a time where AI can generate code, design ideas, and occasionally plausible answers on demand, the need for human critical thinking is greater than ever. Even the smartest automation can’t replace the ability to ask the right questions, challenge assumptions, and think independently at this time.

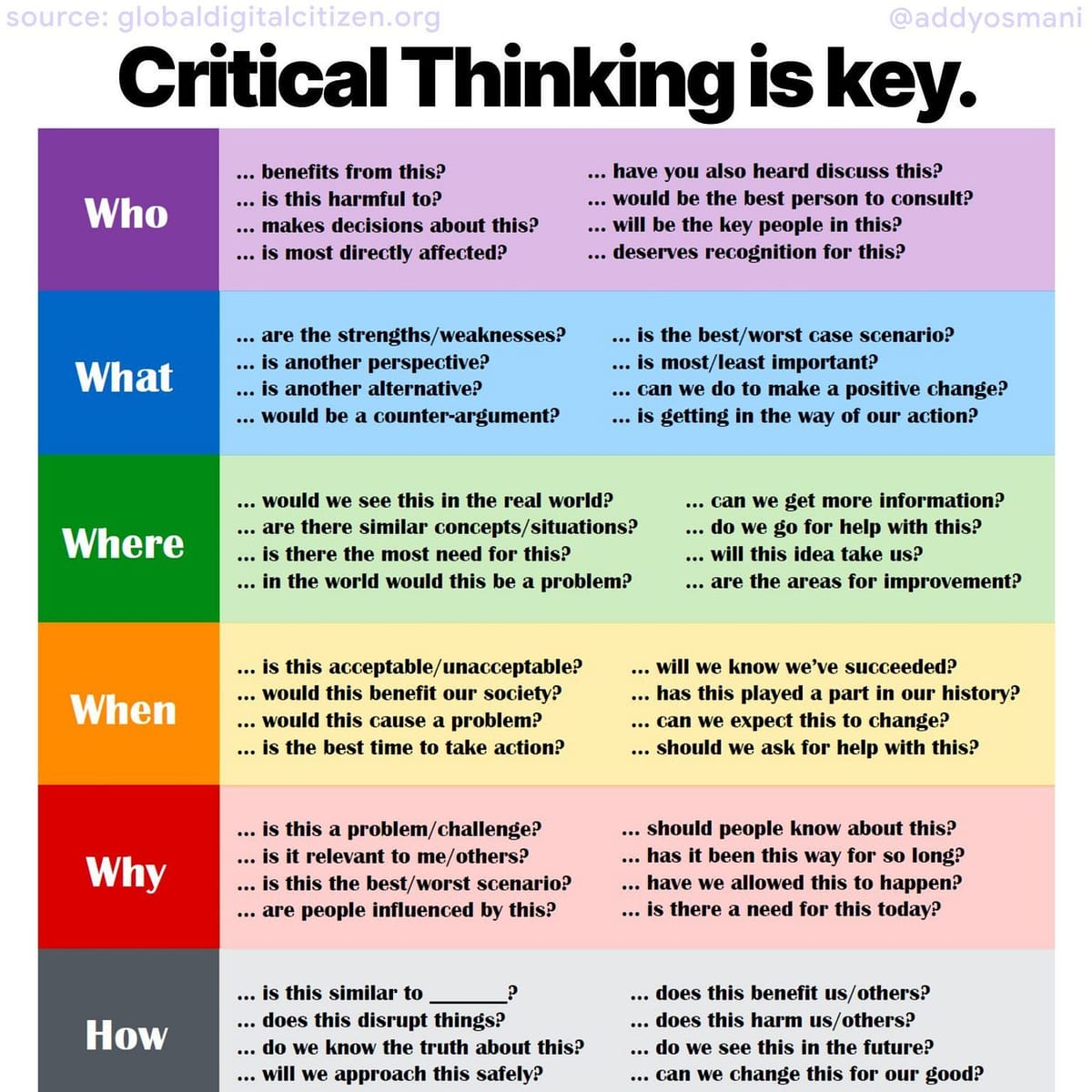

This essay explores the importance of critical thinking skills for software engineers and technical teams using the classic “Who, what, where, when, why, how” framework to structure pragmatic guidance.

[

](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!b1bu!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F22c3b29f-fdec-4f47-8ab2-ca0804a30ed4_1536x1536.jpeg)

tl;dr: Critical thinking checklist for AI-augmented teams

-

Who: Don’t rely on AI as an oracle. Verify its output.

-

What: Define the real problem before rushing to a solution.

-

Where: Context is king. A fix that works in a sandbox might break in production.

-

When: Know when to use a quick heuristic (triage) vs. deep analysis (root cause).

-

Why: Use the “5 Whys” technique to uncover underlying causes.

-

How: Communicate with evidence and data, not just opinions.

We’ll dive into how each of these question categories applies to decision-making in an AI-augmented world, with concrete examples and common pitfalls. The goal is to show how humble curiosity and evidence-based reasoning can keep projects on track and avoid downstream issues.

Who: Involve the right people and perspectives

Who is involved in defining or solving the problem? In technical projects, critical thinking starts by identifying the who.

This means knowing who the stakeholders are (e.g. engineers, product managers, users, domain experts) and making sure the right people are engaged in decision-making. Problems in engineering for example are rarely solved in isolation – they affect users and often span multiple teams. A critical thinker asks: Who should we consult or inform? Who might have relevant expertise or a different perspective? Including diverse viewpoints is essential.

Otherwise, teams risk falling into groupthink, where everyone converges on the same idea and dissenting opinions are silenced. Groupthink can fool a team into validating only their aligned views without questioning if those views rest on good data or sound assumptions. To counter this, effective teams encourage questions from all members and even bring in outsiders for fresh eyes. In short, who is in the room (and who isn’t) can make or break the objectivity of technical decisions.

Who should we listen to – human or AI? In the age of AI assistants, we must also critically assess who an answer is coming from. Is it the output of a large language model or a seasoned colleague? An AI might confidently provide an answer that sounds authoritative, but remember it’s a statistical engine. Who “said” it matters.

A critical thinker treats an AI’s output as just another input to examine, not an oracle. If an entity (like an AI) hands us a plausible-sounding answer, our human tendency is to accept it and not dig deeper. This cognitive laziness isn’t new – it’s a general human weakness to take the easy, “sounds good” solution and run with it. But in engineering, blindly trusting an answer can be dangerous. If an AI code assistant suggests a code snippet or architecture, ask: Who authored this suggestion? Does the AI actually understand our context? Treat AI outputs as if coming from an inexperienced intern – verify everything.

For example, if Cursor provides a code fix for a bug, a critical engineer would review that code thoroughly and test it, just as they would review a junior developer’s work. The who question reminds us that accountability and understanding lie with the humans, regardless of AI involvement.

Who is responsible and who is affected? Finally, critical thinking means staying aware of who will be affected by technical decisions. Shipping a quick-and-dirty fix might satisfy a manager in the short term, but who will maintain the code later? If a system fails, who bears the cost – is it the end-users, the on-call engineers, the company’s reputation?

Considering the human impact grounds our problem-solving in reality. It fosters humility – a recognition that our decisions affect real people and that we ourselves don’t have all the answers. Great engineers and product people cultivate this humility. They know there’s always more to learn and that no single person has the complete picture. By adopting a posture of learning and asking colleagues questions, they fill in their knowledge gaps and catch mistakes early.

In practice, this might mean a backend developer double-checks a feature’s impact with a frontend teammate (“Could this API change break the mobile app?”) or a developer seeking a security review from the infosec team rather than assuming “it’s probably fine.” In short, critical thinking in teams is a social endeavor: it thrives when who is involved includes a mix of people willing to question each other and themselves.

What: define the real problem and gather evidence

What problem are we actually trying to solve? This is perhaps the most important question. A classic pitfall in engineering is rushing to solve something without confirming it’s the right thing.

In fact, Harvard Business Review has emphasized that rigorously defining the problem upfront ensures we address the right challenges and avoid wasted effort. In practice, this means taking time to clarify requirements and success criteria. Imagine a scenario: a product manager requests “an AI feature to summarize user data”. Jumping straight to coding a summarization algorithm would be premature before asking what the end goal is. Is the goal to help users understand their data trends? If so, maybe the “right problem” is actually that users are overwhelmed by raw data, and the solution might involve better visualization rather than just a summary.

Critical thinking urges us to explicitly articulate the problem and question initial assumptions. Our natural instinct is to go into “problem-solving mode” immediately, but this tends to lead us to quick, surface-level fixes rather than more strategic and thoughtful solutions. In other words, if we don’t slow down to define what needs solving, we risk fixing a symptom or a poorly-understood issue. A thoughtful engineer will ask early: “How do we know we’re solving the right problem?” – a simple question that can save immense time and prevent downstream headaches.

Concretely, defining what the problem is involves gathering evidence and facts. For example, suppose users are complaining that a system is “slow.” Rather than blindly optimizing random code, a critical thinker will ask: What is slow, exactly? Is it page load time, a specific query, or the entire app? What evidence do we have? Maybe logs show one database query is taking 5 seconds. That frames the problem clearly: improving that query’s performance. Similarly, in debugging scenarios, asking “What changed?” when something broke often points to the cause – a recent deployment or config update. This investigative mindset ensures we tackle the actual cause rather than just the first guess.

What evidence supports our solution or conclusion? Critical thinking in engineering is fundamentally about evidence-based decision making. It’s not enough to have an idea but we need to justify it with data or logical reasoning. Always ask: “Does the evidence support this conclusion?” For instance, if an AI model suggests that a bug is due to a null pointer exception, don’t accept it at face value – check the logs or write a unit test to confirm. If a performance test indicates improvement, verify the results on multiple runs or environments. In modern AI-assisted development, this is especially vital.

Large language models (LLMs) often produce answers that sound correct. They’re excellent at sounding confident, which can trick even experienced engineers.

>

> If some entity gives you a good enough result, probably you aren’t going to spend much time improving it unless there is a good reason to do so. Likewise you probably aren’t going to spend a lot of time researching something that AI tells you if it sounds plausible. This is certainly a weakness, but it’s a general weakness in human cognition, and has little to do with AI in and of itself. - Hacker News

>

However, a plausible answer isn’t necessarily a true one. LLM answers are “almost always” plausible-sounding but with no guarantee of being correct – a tremendous flaw with real consequences. A critical thinker treats any proposed solution (whether from AI or a teammate) as a hypothesis to be tested, not a fact. They gather evidence to confirm or refute it. This might involve running an experiment, collecting metrics, or searching for analogous past incidents.

Consider the example of evaluating an AI-generated code snippet. Suppose Cursor provides a solution for timezone conversions. Instead of simply copy-pasting and assuming validity, a critical developer tests it against various formats and edge cases. If they discover the code fails on complex offsets, this evidence dictates the next step- perhaps switching to a dedicated library. By asking, “What data supports this?”, engineers avoid the trap of confirmation bias.

Instead, they actively look for falsifying evidence. In technical debates, confirmation bias might lead someone to defend their initial design choice and ignore alternative approaches. The antidote is to seek out data or feedback that challenges your idea: if you believe a new feature improved load time, also look at any cases where it regressed performance. What we know (and don’t know) should drive decisions, not just what we feel. Good critical thinkers are almost like scientists – they gather facts, run tests, and let evidence rather than ego determine the path forward.

Where: consider context and scope

Where does this problem occur, and where will a solution apply? Context is everything in engineering. A fix that works perfectly in one environment might fail in another. Critical thinking means being mindful of where our assumptions hold true. Engineers should ask: Where is the boundary of this issue? Where in the system or workflow are we seeing the effects?

For example, if an AI ops tool flags an anomaly in system metrics, we should pinpoint where – which server, which module – before reacting. A spike in CPU on one microservice doesn’t mean the whole system is failing. By localizing where the problem lives, we avoid over-generalizing or deploying unnecessary global “fixes.” Similarly, consider where a solution will be used. Is the code running on a user’s low-powered smartphone or on a beefy cloud server? The context might dictate very different approaches. A critical thinker is always aware of the environment: “Where will this code run? Where are the users encountering difficulties?”

Where are the gaps in our knowledge? Asking “where” also means identifying where we need more information. If we’re debugging a distributed system, we might realize we don’t know where a specific request fails – is it at the client, the API gateway, or the database? That’s a cue to gather more data (e.g. add logging at various points) to determine the location of failure. Similarly, if a product idea is being discussed, critical thinking prompts us to ask where in the user journey this idea fits. This prevents solving a non-issue; perhaps the “cool feature” is addressing a part of the app that users rarely visit. Knowing where helps allocate effort to where it matters most.

To illustrate, imagine planning an experiment for a new feature rollout. A critical question is: Where will we test it – in a staging environment, with internal users, or as a small percentage A/B test in production? Each context has pros and cons. Testing in a realistic environment (like a small percentage of live users) may reveal issues that an isolated lab test won’t. On the other hand, some experiments should stay in a sandbox to avoid impacting real users. By explicitly considering where an experiment runs, engineers ensure they approach testing with appropriate rigor given the constraints. It’s easy to get false confidence from a perfect lab result that doesn’t hold in the messy real world.

Finally, “where” can be metaphorical: Where could this solution cause side effects? Where might this decision have downstream impact? Thinking a few steps ahead is a hallmark of seasoned engineers. For example, when modifying a shared library, ask where else that library is used. This way, you anticipate ripple effects and can check those places or alert those teams before problems occur. In sum, contextual awareness – spatial, environmental, and systemic – is a key part of critical thinking. It prevents tunnel vision. Great engineers don’t just solve a problem; they solve the problem in the right place and with full awareness of the setting.

When: timing, timelines, and when to dive deep

When did or will something happen? The dimension of time is crucial in technical work. Critical thinking involves asking when both in diagnosing issues and in planning work. In troubleshooting, understanding when a bug first appeared or when a system behaves differently often reveals the cause. (“The system crashed at 3 AM last night – what happened around that time?” Perhaps a nightly job or a deployment coincided with the crash.) Experienced engineers habitually ask: “When did it last work? What’s changed since then?” This line of questioning is often more effective at finding the root cause than blindly guessing. It ties into evidence gathering – a deploy timeline or version history might show exactly when a faulty piece of code went live.

When should we apply more rigor, and when is a quick heuristic enough? Not every decision warrants days of analysis; part of critical thinking is knowing when to go deep. In engineering, we constantly balance thoroughness against time constraints. Project deadlines and on-call incidents can create immense pressure to act quickly. Under stress or tight timelines, humans tend to rely on intuition and mental shortcuts – what cognitive scientists call heuristics. These are useful, but they also open the door to biases and mistakes.

Research at NASA has noted that when engineers are under stress or have limited time, they make faster decisions that are more prone to error than those made with time to reflect. This doesn’t mean we can always avoid urgency, but it means we should acknowledge the risk. A critical thinker under time pressure will consciously slow down on the most crucial aspects of the decision. For instance, if you’re debugging a production outage at 2 AM, you might use a quick fix to get the system running (that’s a heuristic – e.g. restart a service). But a critical mindset means you’ll also note, “This is a band-aid. I need to investigate the root cause in the morning.” In other words, know when to apply a temporary fix and when to invest in a permanent solution.

Approaching rigor with limited time often involves triage: prioritizing which questions need deep answers now and which can be answered later. A useful prompt is, “How do we approach this with rigor given time constraints?” For example, in planning a new feature under a tight deadline, critical thinking might lead a team to identify the riskiest assumption and test it early (even in a quick-and-dirty way), rather than trying to perfect every detail. They focus on when each piece of information is needed. Is it okay to decide the UI later, but crucial to validate the algorithm now? If so, time is allocated accordingly.

Good critical thinkers also develop a sense of timing for interventions. When should we ask for help? If a problem remains unsolved after a certain amount of time, a critical engineer knows it might be time to get a second pair of eyes or escalate to a wider team discussion. When should we pause and reconsider? On teams practicing Agile, this might be at sprint boundaries or before major releases – essentially built-in “when” checkpoints to ask if they’re on the right track. And when have we done enough analysis? There is a point of diminishing returns.

Being rigorous doesn’t mean being paralyzed by analysis. It means doing the right amount of thinking for the decision at hand. As an example, if you have a day to debug an issue, spending the first 4 hours to methodically gather data is wise; spending 23 hours to get a perfect answer might mean missing the deadline. Critical thinking helps balance these through self-awareness: knowing when you’re falling into analysis paralysis versus when you’re leaping to conclusions too soon.

Why: questioning motives, causes, and rationale

Why are we doing this? The “why” questions get to the heart of motivation and causality. In an engineering context, constantly asking why serves two big purposes: (1) ensuring there’s a sound rationale for actions (so we’re not just doing things because “someone said so”), and (2) drilling down to find root causes of problems rather than treating symptoms. A critical thinker faced with a task – say, implementing a new AI tool – will ask: “Why do we need this tool? What problem will it solve and why is that important?”

If the best answer the team has is “because it’s trendy” or “our competitor has it,” that should spark concern. Chasing buzzwords without a clear why can lead teams to invest in solutions that don’t actually address their users’ needs. On the other hand, articulating a strong why (e.g. “to reduce the time users spend analyzing their data by automating summaries”) aligns the team on the real goal. It fosters independent thinking – an engineer confident in the why can independently make better decisions during implementation, because they understand the end goal deeply rather than just following orders.

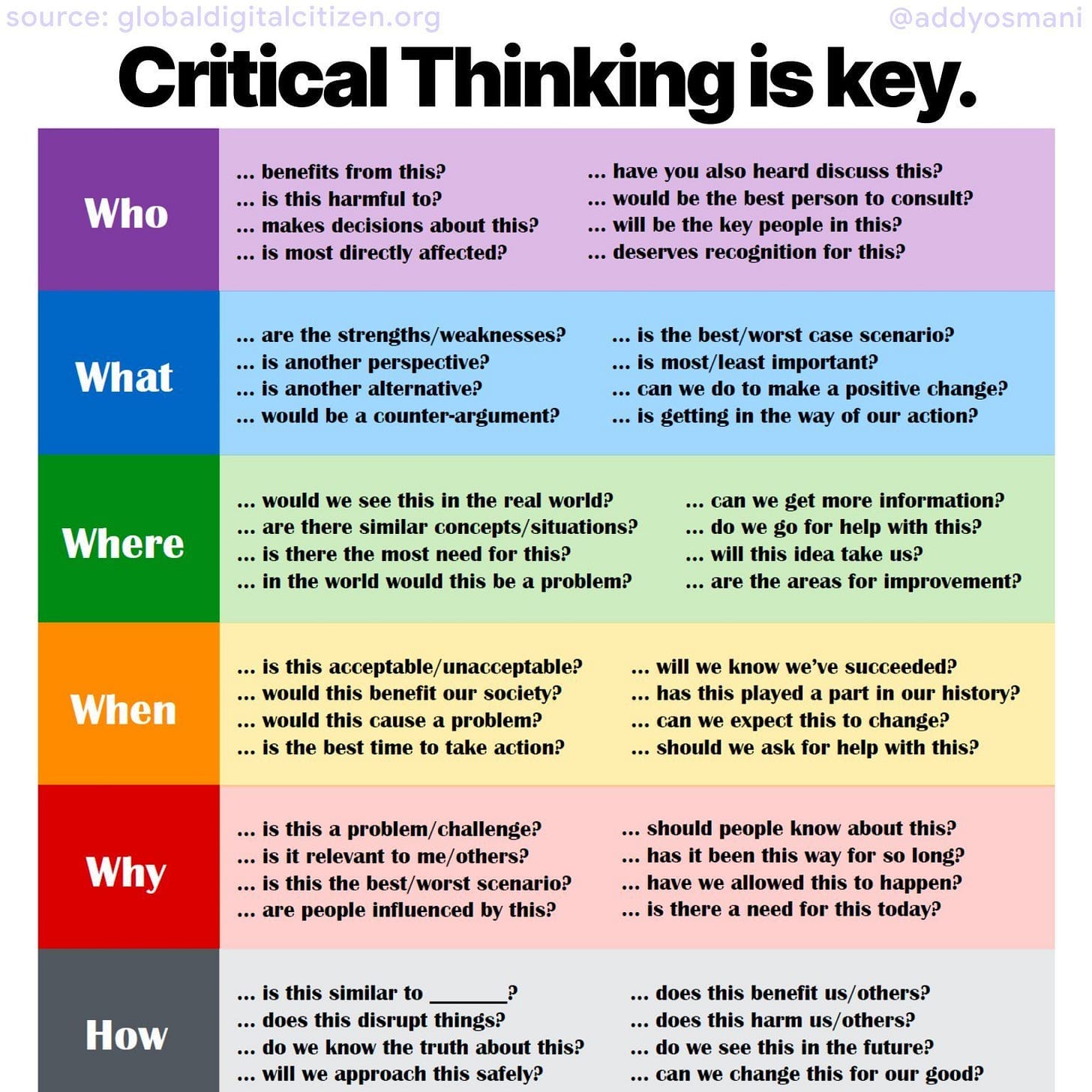

Why did this happen? When something goes wrong (or right), asking “why” repeatedly is a proven technique to get beyond superficial answers. In fact, the Five Whys technique in root cause analysis is essentially institutionalized critical thinking – it forces you to peel back causes layer by layer. The idea is to avoid jumping on the first explanation and instead uncover the chain of causality.

[

](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!-ez0!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F18628494-1acb-4eda-bcf0-e4500d5ff54d_1920x1080.webp)

For example, imagine a machine learning model’s accuracy suddenly drops. A naive response might be, “The model is bad, retrain it.” A critical approach would ask: “Why did the accuracy drop? Because the input data distribution changed.” Why did that happen? Perhaps a new data source was added. Why was that not accounted for? Maybe the data pipeline lacked a validation for distribution shifts. By the time you’ve asked “why” five times (or as many times as needed), you likely have a much clearer picture – maybe the real root cause was a flawed monitoring process that failed to catch the data drift early.

The difference is significant: a quick fix might simply involve retraining the model (temporarily addressing the symptom of low accuracy), whereas the Five Whys approach could lead you to enhance the monitoring system, thus preventing the problem from recurring. As one guide on the 5 Whys method notes, this technique “aims to get to the heart of the matter rather than just addressing surface-level symptoms,” encouraging teams to move beyond quick fixes toward sustainable solutions.

However, asking why can be a double-edged sword if we’re not cautious. Humans are vulnerable to biases when seeking answers. A common pitfall is confirmation bias — we may latch onto a convenient explanation that aligns with our preconceptions and stop investigating further. For example, an engineer might assume “The server crashed because of a memory leak, which has happened before” and overlook other possibilities such as a new configuration change, simply because the memory leak fits their mental model. If they don’t seek evidence to disconfirm their hypothesis about the memory leak, they may miss the true root cause.

---

For teams working in complex systems — whether debugging production issues, refining algorithms, or generating AI-powered content — combining structured problem-solving methods like the Five Whys with robust evidence-gathering can be transformative. In fact, modern open-source platforms like AiToEarn官网 integrate AI content generation with tools for monitoring, analytics, and multi-platform publishing, enabling creators and engineers alike to iterate, test, and distribute improvements efficiently. This fusion of systematic inquiry and scalable tools helps prevent recurring problems and maximizes the impact of AI-driven work.

The earlier-mentioned plunging-in bias is another “why” trap: it’s the tendency to rush into solving a perceived problem without fully understanding it. Studies have found that this bias – jumping to conclusions and imposing pre-determined solutions – leads to addressing symptoms rather than root causes in about half of failed decisions studied. In other words, not asking “why” enough (or not the right why) can sink projects. The Harley-Davidson company in the 1980s famously misdiagnosed why they were losing market share, blaming external factors and thus implementing wrong solutions, when the real issues were internal practices. It took years for them to correct course, exemplifying how failing to pin down the true “why” can prolong pain.

Good critical thinkers are almost relentlessly curious about why. They maintain a humble curiosity – an openness to finding out that their initial assumption was wrong. They ask questions like: “Why do we believe this approach will work? Is it because of actual data or just our gut? Why are users asking for this feature – what’s the underlying need?” By drilling into reasons, they often catch logical gaps or uncover hidden requirements. Importantly, they also communicate the why behind decisions to others, which helps teams stay aligned and spot flaws. If you can’t clearly explain why a particular technical decision was made, that’s a red flag – either the decision lacks solid reasoning or that reasoning isn’t shared (both are dangerous). On the flip side, when everyone understands the rationale (the why), they can independently verify if new developments still support that rationale or if it needs revisiting.

How: apply rigor and communicate clearly

After exploring “who, what, where, when, why,” the final question is “How do we actually practice critical thinking day to day?” This is about the methods and mindset – how to approach problems rigorously yet efficiently, and how to carry solutions through with clear communication. Good critical thinkers tend to have a systematic approach. They formulate questions clearly, validate evidence, and communicate solutions logically. Let’s break this down:

-

How to approach problems methodically: Often it starts with asking better questions. Instead of vague queries, they ask specific, open-ended questions that lead to insight. For example, rather than “Is this design good?”, a critical thinker might ask “How does this design address the user’s primary need and how could it fail?” It’s important to avoid loaded or leading questions that just confirm what we already think. Maintaining an open mind and probing for details yields much more useful information. A practical habit is to enumerate what you know and what you don’t know, then plan how to test or learn the latter. Think like a scientist: if you have a hypothesis (e.g. “the database is the bottleneck”), figure out how to prove or disprove it (perhaps by profiling or looking at query times). This structured interrogation of problems is at the core of critical thinking.

-

How to validate evidence and avoid bias: Once you have data or answers, a critical thinker validates them. Does the data actually support the conclusion, or are there alternative interpretations? This might mean cross-checking metrics from two sources, reproducing a bug in a test environment to ensure it’s not a fluke, or getting a code review for an assumption you’ve made. It also means being aware of your own biases. As discussed, if you find yourself gravitating to an explanation too quickly, pause and ask, “Am I considering all the evidence, or just the bits that confirm my theory?” One strategy is actively seeking contradictory evidence. If you think a new feature improved retention, look at any cohort where retention didn’t improve – what’s different there? By welcoming negative data, you ensure you’re not kidding yourself. This is essentially a quality assurance mindset but applied to thinking: test the robustness of your ideas like you test your code. Additionally, frameworks and checklists can help maintain rigor. Some teams, for example, use a premortem exercise (imagining a future where the project failed and writing down reasons why) to surface potential issues and assumptions that weren’t initially considered. Such techniques enforce a more critical evaluation of a plan before it’s executed.

How to Communicate Solutions and Reasoning

A brilliant solution has little value if it can’t be clearly communicated and effectively implemented by the team. Critical thinking truly stands out in how solutions are explained.

Strong engineers structure their explanations logically:

- Start with the problem definition — clarify what the issue is and why it matters.

- Present the proposed solution — outline how you plan to address the problem.

- Support with evidence or reasoning — explain why this approach works, including the data or logic behind it.

They explicitly state any assumptions and describe the trade-offs considered. This structure helps others quickly understand the proposal and also acts as a final self-check: if you can’t express your idea clearly, your thinking may still be incomplete.

Importantly, critical thinkers rely on facts and data, not just subjective impressions. As one engineering leadership article notes, humble engineers prefer facts over opinions — they will cite data (“this change improved load time by 25% as measured on the dashboard”) rather than making boastful or vague claims. This evidence-driven approach builds trust with colleagues and stakeholders, making it far easier for the team to rally behind a solution.

Clear communication also means listening and actively inviting feedback. A critical thinker doesn’t deliver a one-sided monologue — they open the floor for questioning and discussion:

> “Here’s what I propose and why. Does anyone see any gaps in this reasoning or have concerns?”

By encouraging colleagues to challenge assumptions, spot risks, or uncover overlooked factors, the solution becomes more robust and gains wider agreement. This collaborative approach ensures ideas are strengthened by diverse perspectives, rather than simply pushed through by the loudest voice.

Finally, for those who want to take structured, evidence-based communication further — especially when sharing solutions or insights across teams, projects, or even public platforms — tools like AiToEarn can help streamline the process. AiToEarn is an open-source global AI content monetization platform that allows creators and professionals to use AI to generate, publish, and monetize content across multiple platforms such as Douyin, Kwai, WeChat, Bilibili, Rednote (Xiaohongshu), Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, Threads, YouTube, Pinterest, and X (Twitter). With built-in support for AI content generation, multi-platform publishing, analytics, and even AI model ranking, it provides a way to efficiently bring well-reasoned, data-backed ideas to a much wider audience — while potentially creating new revenue streams for thoughtful work.

Finally, “How do we ensure we’re continuously improving our critical thinking?” This meta-question is worth a thought. The answer is practice and reflection. Just as we do retrospectives for projects, doing mini-retrospectives on decisions can sharpen thinking skills. For instance, if a rushed decision led to a bug, a team can analyze: how did we miss it, and how can we catch such things next time?

Over time, engineers build a mental library of lessons learned (e.g. “Remember to check X, because last time we assumed and it burned us”). Many top engineers also cultivate habits like reading post-mortems from other companies’ failures or studying cognitive biases to become familiar with traps they might fall into. Critical thinking isn’t a one-and-done checkbox; it’s a continuous, career-long discipline of staying curious, humble, and evidence-driven.

Conclusion

As AI gets increasingly used, critical thinking is not optional, but essential.

We should ask Who should be involved, What is the real problem, Where is the context, When to dig deeper, Why something is done, and How to do it properly. By using this classic framework pragmatically, technical teams can navigate complexity with clarity.

It means a culture where independent thinking is valued: team members feel safe to question a proposed solution (“How do we know this is truly the fix and not a band-aid?”), to challenge assumptions (“Why are we sure the users want this feature?”), and to demand evidence (“Does the data actually show an improvement, or are we seeing what we want to see?”). Embracing humble curiosity – the idea that no matter how experienced we are, we could be missing something – keeps engineers from falling prey to confirmation bias or overconfidence.

Critical thinking also protects against the allure of quick fixes. It’s understandably tempting to patch a problem and move on, especially under pressure. But as we’ve seen, failing to think critically about a quick fix can mean the same problem resurfaces later or, worse, that we fix the wrong thing entirely. By asking the tough questions upfront and validating before acting, we actually save time and trouble in the long run. We avoid downstream issues by catching them upstream – whether it’s discovering a design flaw before code is written or realizing an AI’s output is flawed before it reaches customers.

In conclusion, while AI and automation will continue to evolve and handle more routine work, critical thinking remains an uniquely human advantage. It’s how we ensure that we’re solving the right problems, in the right way, for the right reasons.

[

](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!54oK!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7e90581d-19f6-4a27-bec6-26e9ce06b3c5_5246x3496.jpeg)