Social Terms: Definitions, Evolution, and Policy Impact

## Social Terms: Definitions, Evolution, and Policy Impact Social terms are the shared vocabulary that shapes public understanding, dialogue, and deci

Social Terms: Definitions, Evolution, and Policy Impact

Social terms are the shared vocabulary that shapes public understanding, dialogue, and decision-making. This concise guide to social terms introduces key definitions, traces historical evolution, and explains how language influences policy and public opinion—so leaders, educators, and communicators can use social terminology with clarity and care.

Introduction to Social Terms and Their Importance in Modern Discourse

Social terms are the vocabulary of public life: the words and phrases we use to describe identities, communities, social conditions, and political realities. From “equity” and “privilege” to “social safety net” and “algorithmic bias,” social terms help people communicate values, diagnose problems, and propose solutions. They influence how we perceive each other, shape cultural narratives, and often serve as the foundation for public policy debates.

Why language frames understanding

Why do social terms matter? Because language frames understanding. Whether we are discussing healthcare access, policing, climate justice, or education, the terms we choose can open doors to empathy and evidence—or close them via misinterpretation or polarization. In workplaces, classrooms, and legislative chambers, shared definitions reduce confusion and conflict. In contrast, inconsistent or politicized usage can stall collaboration or enable misinformation.

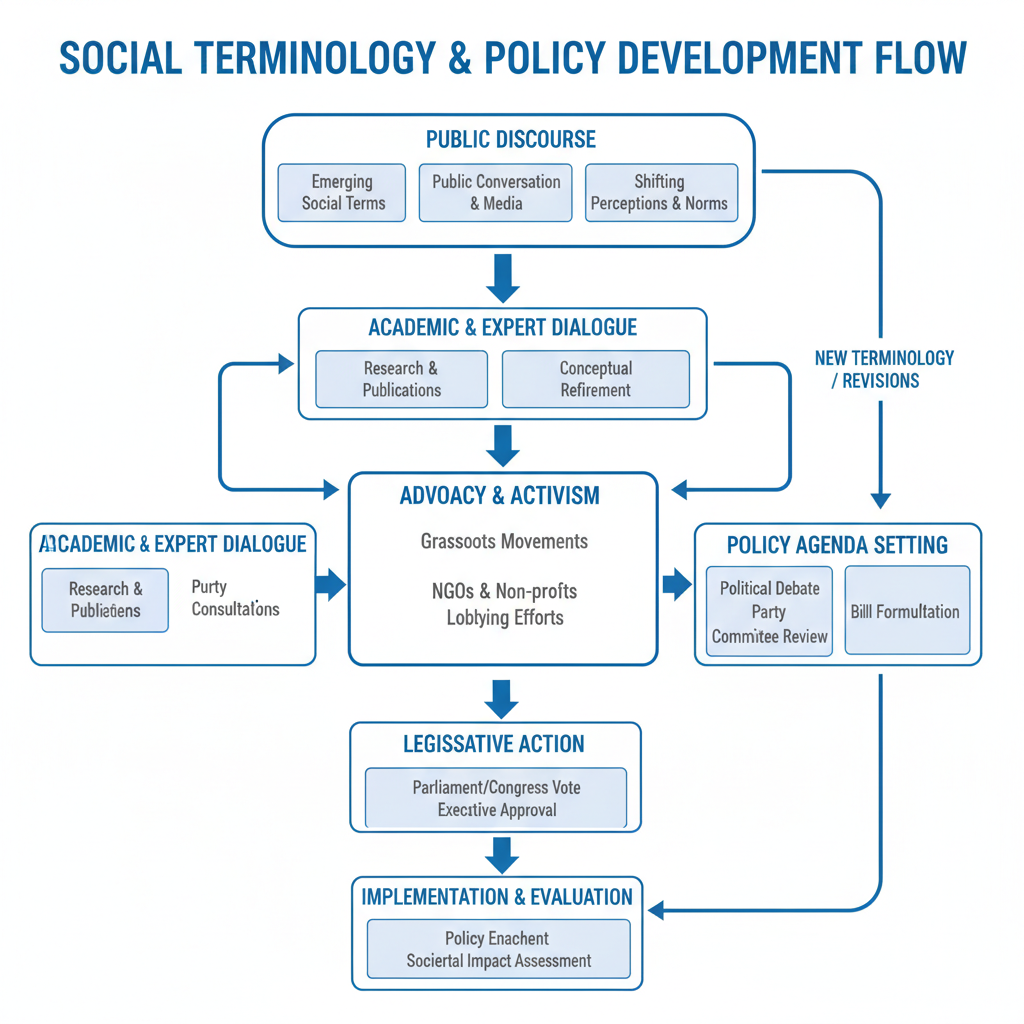

A dynamic, evolving lexicon

In modern discourse, social terms are dynamic. They evolve as communities gain visibility, research sheds light on systemic phenomena, and technologies introduce new contexts for social interaction. This evolution is healthy—it reflects learning and changing realities—but it also calls for critical listening, careful definition, and constant updating.

Historical Evolution of Common Social Terms

Social language has never been static. Across decades and regions, terms adapt to reflect new understandings, power shifts, and cultural priorities. Consider a few illustrative trajectories:

- Minority → Historically used to describe groups with relatively less political power or representation, this term’s scope and sensitivity have been debated. Alternatives like “historically marginalized groups” or “underrepresented communities” aim to emphasize power and history rather than numeric size.

- Gender → Once treated as a binary biological category, gender has evolved toward recognizing identity, expression, and spectrum. This shift acknowledges lived experiences and challenges rigid frameworks, influencing workplace policies, healthcare practices, and education.

- Race and ethnicity → Terms describing racial and ethnic identities have changed alongside civil rights movements and social science research. Contextual specificity (e.g., “Black,” “Latinx,” “Indigenous”) and agency in self-identification have gained prominence.

- Welfare → Framed in different eras as either safety net or dependency, the word “welfare” has been central to policy reform and political narratives, especially in the 1990s United States context.

- LGBTQIA+ → Expanded acronyms reflect increased recognition of identities and orientations, alongside advocacy for inclusive language in law, healthcare, and education.

- Disability → The shift from “handicapped” to “disabled,” and more recently discussions of “disabled person” vs. “person with a disability,” demonstrate ongoing debates about identity-first and person-first language.

Policy and institutional implications

These trajectories reveal how social terms reflect historical struggle, research, and lived realities. When terms change, policy instruments and institutional practices—data collection, funding criteria, compliance frameworks—must often change with them.

Categories of Social Terms: Cultural, Political, and Economic Contexts

Social terms can be grouped by context to clarify their functions and implications:

- Cultural: Identity, representation, norms, and belonging.

- Political: Governance, rights, public debate, and institutional power.

- Economic: Labor, distribution, inequality, and resource access.

Cultural, political, and economic signals

To help situate usage, the table below maps categories to common examples and policy arenas.

| Category | Focus | Common Social Terms | Typical Policy Arenas |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural | Identity, representation, norms, community | Identity, intersectionality, cultural competency, representation, inclusion | Education curricula, media standards, diversity initiatives, public arts |

| Political | Power, rights, institutions, participation | Civic engagement, disenfranchisement, civil liberties, polarization, populism | Election law, policing, civil rights protections, governance reform |

| Economic | Labor, distribution, welfare, inequality | Social safety net, wealth gap, living wage, precarity, social mobility | Tax policy, labor law, public benefits, housing and healthcare access |

This contextual map is a practical tool for educators, communicators, and policymakers. It clarifies how a term functions in discourse and helps anticipate which stakeholders may be impacted.

Key Social Terms and Their Definitions in Everyday Communication

The following definitions are concise starting points. In practice, usage varies by community and context, so always defer to documented local conventions and self-identification.

Core definitions and usage notes

- Identity: A person’s self-ascribed characteristics and affiliations, including race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, nationality, religion, and more. Identities are personal but also structured by social forces.

- Equity vs. Equality: Equality is treating people the same; equity is allocating resources and opportunities based on need and historic exclusion so outcomes can be fair.

- Inclusion: Practices and norms that enable people of diverse identities to participate fully and authentically; goes beyond presence to consider power and belonging.

- Privilege: Unearned advantages conferred by social structures to certain identities or groups; often invisible to those who hold it.

- Marginalization: Systemic exclusion or devaluation of people based on identity or status; manifests in institutions, policies, and cultural narratives.

- Systemic racism: Racism embedded in social institutions and policies producing disparate outcomes, regardless of overt individual intent.

- Social capital: Resources gained from networks, trust, and norms that facilitate collective action and personal opportunity.

- Civic engagement: Participation in public life (voting, attending meetings, advocacy) that shapes collective decisions.

- Polarization: The intensification of ideological differences and the reduction of cross-group understanding and compromise.

- Populism: Political rhetoric or movements that claim to represent “the people” against “the elite,” often reshaping social terms to mobilize support.

- Social safety net: Public programs designed to reduce economic insecurity and ensure basic needs (housing, food, healthcare).

- Precarity: Instability in employment, housing, or income that undermines wellbeing and planning.

- Algorithmic bias: Systematic unfairness in automated decision systems due to data, design, or deployment choices.

- Representation: The portrayal and presence of diverse identities in media, decision-making bodies, and influential positions.

- Cultural competency: The ability to interact effectively with people of diverse backgrounds by understanding cultural norms and context.

These definitions aren’t exhaustive. They can be expanded into glossaries with local examples, citations, and usage notes for organizational training.

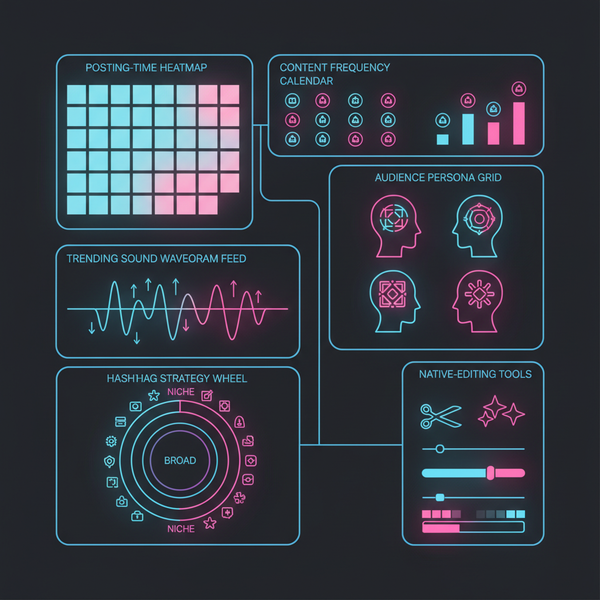

The Role of Media and Technology in Shaping Social Terminology

Media and technology act as accelerants for social terms: they spread vocabulary quickly, transform meaning through context, and amplify certain framings.

Media dynamics and platform effects

- Mass media: Newsrooms, films, and TV define mainstream usage. Editorial choices, sourcing, and headline framing shape public understanding. Style guides (e.g., decisions about capitalization of “Black”) institutionalize norms.

- Social media: Hashtags, memes, and influencer discourse rapidly circulate terms, often compressing complex ideas into slogans. Virality can prioritize emotionally resonant language over nuance.

- Platform governance: Content moderation rules and recommendation algorithms implicitly define which terms are acceptable and which get visibility.

- Data and analytics: Monitoring and categorization of public discourse (e.g., topic modeling, sentiment analysis) can both inform and distort perceptions of how terms are used across communities and geographies.

- AI and generative tools: Language models can propagate dominant framings and biases. Transparent sourcing and community feedback are crucial to avoid misrepresentations.

As technology evolves, terms can gain new meanings (“shadow banning,” “cancel culture,” “digital divide”). Institutional literacy—knowing how algorithms amplify, suppress, or reinterpret language—has become part of modern civic competence.

Intersectionality and How It Informs the Meaning of Social Terms

Intersectionality describes how overlapping identities (such as race, gender, class, disability, and sexuality) compound experiences of advantage or marginalization. It challenges single-axis analyses and demands nuanced interpretation.

Intersectionality in practice

- Dynamic meaning: The meaning of a social term can shift at intersections. “Safety,” for instance, can mean different things in a conversation about policing depending on a person’s race, class, and neighborhood history.

- Policy design: Intersectional analysis prevents one-size-fits-all solutions. For example, workforce programs that only track gender disparities may miss how race or immigration status affect outcomes.

- Research ethics: Intersectional sampling and analysis avoid erasing subgroup experiences. Aggregated data may obscure inequities within broad categories.

Intersectionality is not only an identity framework; it’s a methodological lens for institutions. In academia, public health, urban planning, and law, intersectional thinking helps define problems more precisely and design interventions that respect lived complexity.

Common Misunderstandings and Misuse of Social Terms

Because social terms carry emotional, historical, and political weight, misunderstandings are common. A few pitfalls to avoid:

Common pitfalls and how to address them

- Treating terms as fixed: Words like “privilege” or “equity” are contextual. Overgeneralizing can cause backlash or confusion.

- Collapsing identity categories: Using umbrella labels without acknowledging internal diversity (e.g., “Asian” without specifying distinct communities) can flatten experiences.

- Assuming intent equals impact: Social harms can occur even without malicious intent. Systemic terms emphasize outcomes, not just motives.

- Using jargon without definition: Technical or activist language can alienate audiences. Provide accessible definitions and examples.

- Framing effects: Linguistic framing (“illegal immigrant” vs. “undocumented person”) influences perceptions and policy preferences.

- Tokenization: Treating representation as purely numerical without considering power and agency undermines inclusion.

To counter misunderstandings, organizations should use living glossaries, audience testing, and inclusive review processes for public communications.

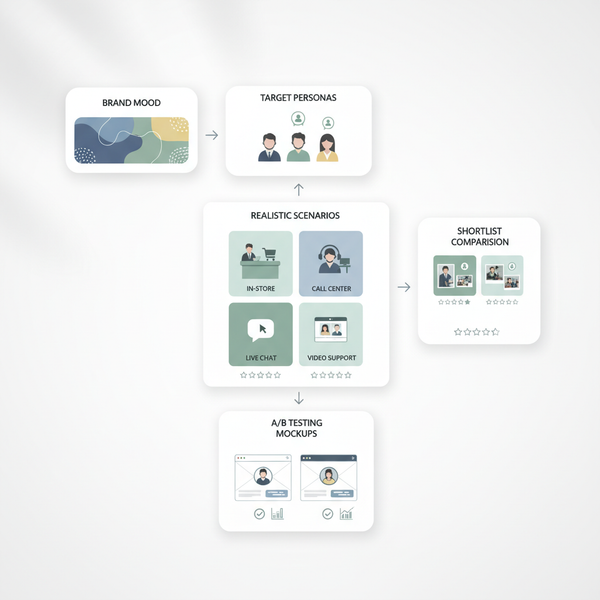

How Social Terms Influence Policy and Public Opinion

Social terms are not merely descriptive; they are instrumental in policy design and political mobilization. Framing matters at each stage of the policy cycle:

- Agenda-setting: Terms define what’s seen as a problem. Saying “housing crisis” rather than “market fluctuation” signals urgency and a collective responsibility to act.

- Policy formulation: Definitions determine eligibility, metrics, and scope (e.g., how “disability” or “family” is defined in benefits programs).

- Adoption and implementation: Clear language facilitates compliance and accountability. Ambiguous terms can create loopholes or uneven enforcement.

- Evaluation: Terms shape which outcomes are measured and valued (e.g., “equitable access” suggests disaggregated metrics by identity).

Framing examples and impact pathways

Examples of framing effects:

- “Defund the police” mobilized some constituencies while alienating others; alternative terms like “reimagine public safety” impacted coalition-building and legislative approaches.

- “Welfare queen” framed social benefits negatively, influencing reform and public attitudes despite limited empirical support.

- “Marriage equality” emphasized fairness and legal consistency, aiding public support in many jurisdictions.

- “Undocumented” vs. “illegal” changed moral valence and policy support in immigration debates.

To visualize framing and potential impact:

| Term/Frame | Primary Narrative | Public Opinion Tendency | Policy Impact Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social safety net | Collective care and resilience | Higher support for benefits | Budget allocation, eligibility expansion |

| Entitlements | Guaranteed benefits, fiscal risk | Mixed; concern over costs | Means testing, reforms to reduce spending |

| Climate justice | Fairness in burdens and solutions | Support among impacted communities | Targeted investments, environmental regulation |

| Public safety | Protection from harm | Broad support, contested means | Budgeting across policing, health, housing |

Policy writers and advocates should treat social terms as instruments: define them precisely, test frames across audiences, and align terms with measurable outcomes.

Adapting to Changing Social Language in the Digital Age

Organizations can build adaptive language practices that respect community standards, support clarity, and keep pace with change. Practical steps include:

- Maintain a living glossary: Host a versioned glossary that documents definitions, examples, and citations. Invite community feedback and update periodically.

- Disaggregate data: Measure outcomes across relevant identity categories to avoid masking disparities.

- Train communicators: Provide workshops on inclusive language, framing effects, and media literacy. Include role-play scenarios for contested terms.

- Audit platforms: Review how moderation and algorithms affect visibility of social terms in official channels.

- Co-create with communities: Involve impacted groups in defining terms used in programs and policies.

Lightweight governance and decision aids

A lightweight, technology-enabled approach:

{

"glossary": {

"version": "1.4.0",

"updated": "2025-09-01",

"terms": [

{

"term": "equity",

"definition": "Adjusting resources and opportunities to achieve fair outcomes.",

"contexts": ["education", "healthcare", "housing"],

"notes": "Differentiate clearly from equality in trainings.",

"examples": [

"Equity-focused budgeting",

"Equitable access to telehealth"

]

},

{

"term": "intersectionality",

"definition": "Overlapping identities that shape experiences of advantage and marginalization.",

"contexts": ["policy analysis", "public health"],

"notes": "Use disaggregated metrics; avoid single-axis reporting."

},

{

"term": "algorithmic bias",

"definition": "Systematic unfairness in automated systems.",

"contexts": ["hiring", "credit scoring", "policing"],

"notes": "Conduct bias audits; document training data sources."

}

]

},

"process": {

"review_cycle_days": 90,

"stakeholders": ["DEI committee", "legal", "community advisory board"],

"approval": "consensus or supermajority",

"public_feedback": true

}

}Teams can also introduce simple decision aids:

Inclusive Language Checklist:

1) Define the term clearly and consistently.

2) Verify community-preferred naming conventions.

3) Explain context (cultural, political, economic).

4) Provide examples showing impact on policy or practice.

5) Test framing with diverse audiences before publication.

6) Document changes and reasons in the glossary.These practices make language governance visible and accountable. They help organizations prevent miscommunication and align terminology with evidence and equity goals.

Conclusion: Building Awareness and Sensitivity Around Social Terms

Social terms are core to how societies reason about identity, justice, and collective action. They evolve with research, culture, and technology, and their meaning is shaped by intersectional realities. When we use social terms carefully—defining them, contextualizing them, and listening to affected communities—we improve communication and reduce friction. We also design better policies, because precise language translates into clearer objectives, fairer eligibility rules, and more meaningful evaluation.

Media and technology now accelerate linguistic change. That makes awareness and sensitivity essential skills for leaders, educators, journalists, and technologists. By maintaining living glossaries, auditing platforms, and co-creating language with communities, we can adapt responsibly in the digital age.

Ultimately, building shared understanding around social terms is not just about words—it’s about the systems and relationships those words describe. Thoughtful language helps us see problems accurately, include people fully, and act with integrity.

Summary and Next Steps

- Social terms shape public understanding, institutional practice, and policy outcomes.

- Meanings evolve; intersectionality and media dynamics affect interpretation and impact.

- Use living glossaries, inclusive review processes, and framing tests to improve clarity and equity.

Call to action: Start a living glossary, train your communicators on inclusive language, and audit your platforms—then revisit terms quarterly to keep your social terminology aligned with community standards and evidence.